Integration

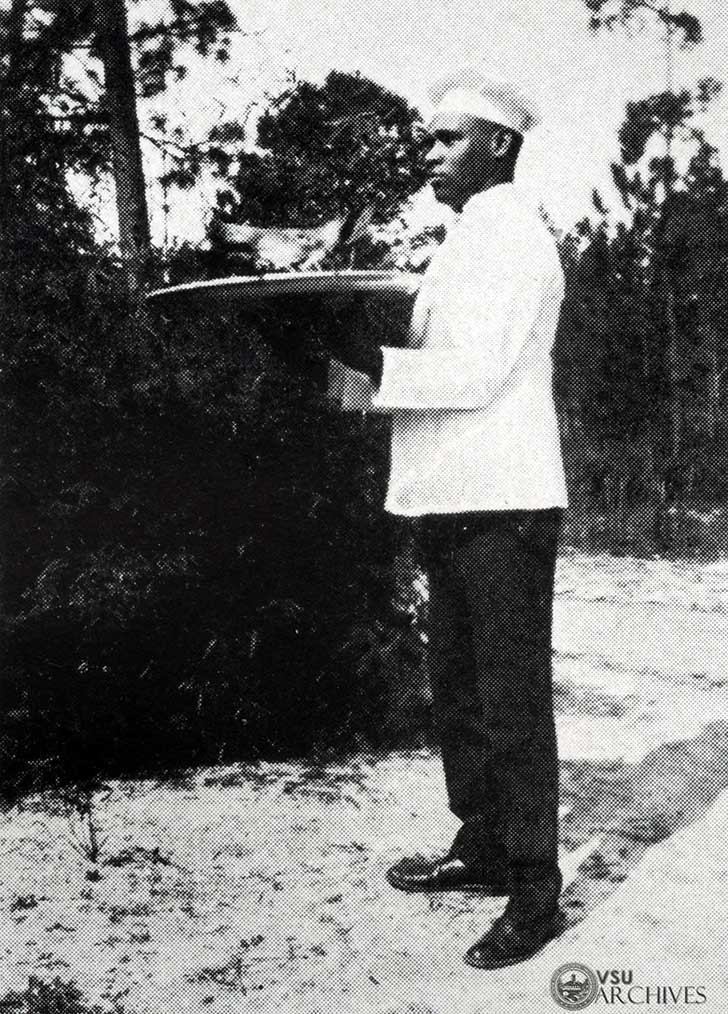

Our Early Days

Prior to 1963, the African American presence at Valdosta State was limited to staff in cleaning, cooking, and maintenance positions. Here, Leroy McCormick, GSWC cook, carries in the boar’s head for the Christmas Festival in 1924. Though the school barred African Americans, it gave financial assistance through loans and grants to some of the children of its African American workers so they could attend historically black colleges.

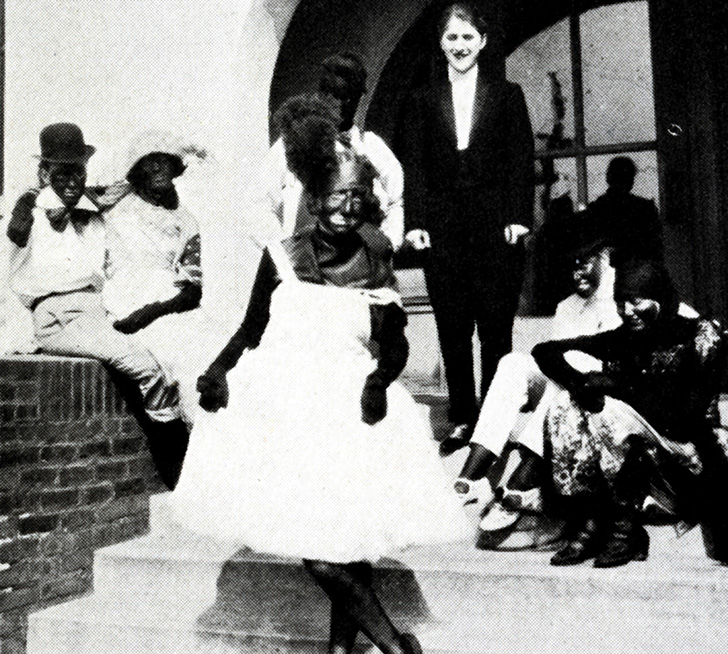

Signs of the Times

The Georgia State Womans College was an institution of its time. Its prejudices reflect the prejudices usual in the first half of the 20th century. A common entertainment, this mistral show was featured in the 1925 Carnival at GSWC.

Cooperation, of a Kind

The University system included traditionally black institutions like Fort Valley State and Georgia Normal and Agricultural College in Albany, and though the administrators occasionally corresponded and visited, the students did not meet. Pictured here is a meeting of the University System Council that took place in January 1936, with college presidents and officers from institutions around the state meeting at Georgia State Womans College.

University of Georgia Council, January 1936. Georgia State Womans College, West Hall.

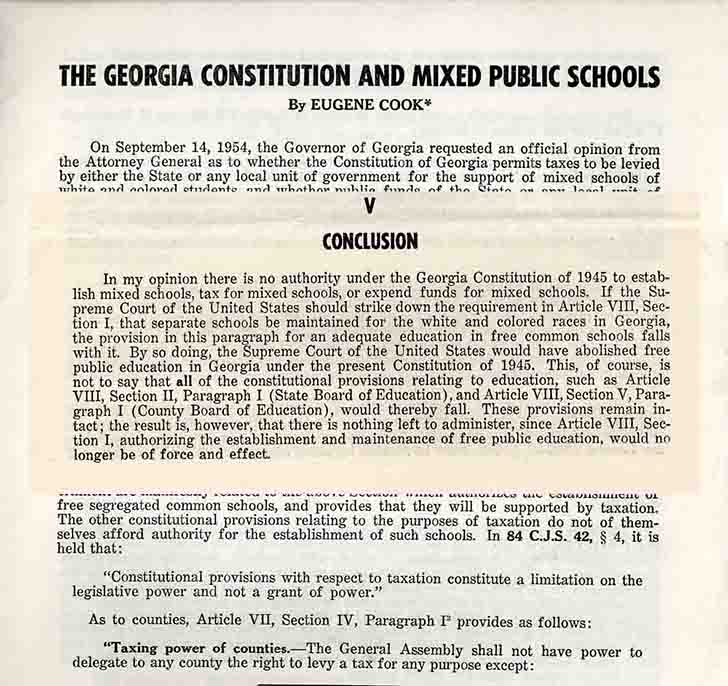

"The End of Public Education!"

In 1954, in the case of Brown versus the Board of Education, the United States Supreme Court decided “that, in the field of public education, the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place.

Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” In the South, this served to harden attitudes and lent itself to outrageous schemes to avoid the decision of the courts. Here is a piece of the document where Governor Herman Talmadge and his attorney general decided, after long research, that desegregation would result in ending public education in Georgia.

At Valdosta things were quiet. During the nine-year period between the Brown case and official desegregation, the student newspaper contained one race-baiting article and one campus incident. To protest prices and hours at the Student Center, a group of students organized a boycott, and during that time some students burned a cross of construction materials one night near West Hall. All involved were quickly expelled and quietly returned to Valdosta.

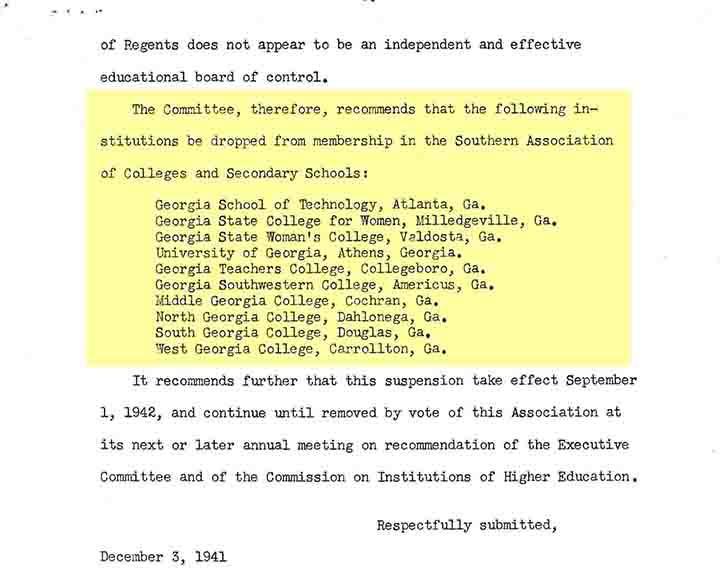

The Cocking Affair

Georgia State Womans College was an unwilling victim of the Cocking Affair, a power struggle between Governor Eugene Talmadge and parts of the University System that occurred in 1941. In an attempt to stamp out what he saw as the possibility of “racial equality” that might arise from a single proposed integrated classroom demonstration at the University of Georgia, Talmadge attempted to fire the professor he considered responsible. When he met resistance from the Board and college presidents, the governor stacked the Board of Regents and fired numerous educators across the state. In response, the Southern Association of Colleges removed its accreditation from all white, state-funded colleges in Georgia in 1942, including GSWC. Because of his meddling with the University System, Talmadge lost the 1942 election to Ellis Arnall, who corrected the situation.

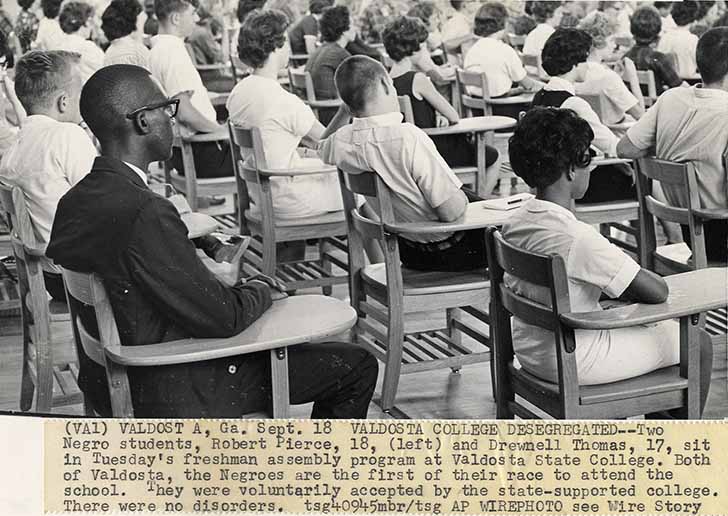

The Integration of Valdosta State College

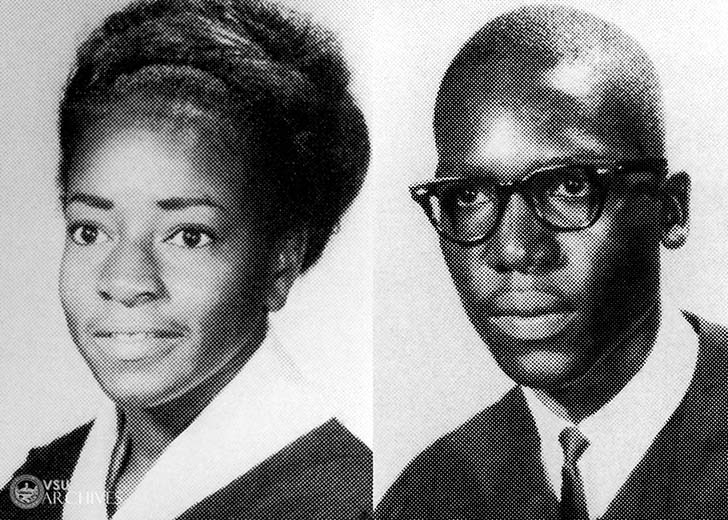

In the early 1960's Georgia's colleges began to integrate, beginning with the University of Georgia in 1961. In 1963, Valdosta State College joined in as it admitted Drewnell Thomas and Robert Pierce, local Valdosta students who met the standards for admission at VSC, despite having attended segregated high schools. Here are Pierce and Thomas at their first freshman assembly on September 18, 1963.

Dr. Thaxton wrote of the peaceful desegregation: "This year for the first time, the college had Negro students in its student body... These two, a local Negro boy and a local Negro girl were the ... two students..eligible for admission... [I, President Thaxton] discussed the possibility of integration with various civic groups and I believe that we had the field rather well prepared for integration when the opening of the college came. An injunction was taken out against me, but very little effort was made to serve [it]... The Students had been registered before they located me. We were threatened with some disorder by a group ... and the group did show up on campus ... however, the presence of a considerable number of State Highway Patrolmen and some local city police officers discouraged this group and they left the campus and there was no disorder of any kind" (VSC Annual Report, 1964, p. 9-10.)

Integration, Year Two

During 1964-1965, the school had the same two African American students that it had the previous year. Dr. Thaxton's comment from 1963 applied: "Students accepted the two Negro students with silence. They were two lonely young people throughout the entire year." (President's Annual Report for VSC, 1963-1964). Both Students back up Thaxton's impression: Thomas referred to the students' attitude as "cold and hypocritical" and Pierce agreed. (Campus Canopy, 4/5/67, p.4).

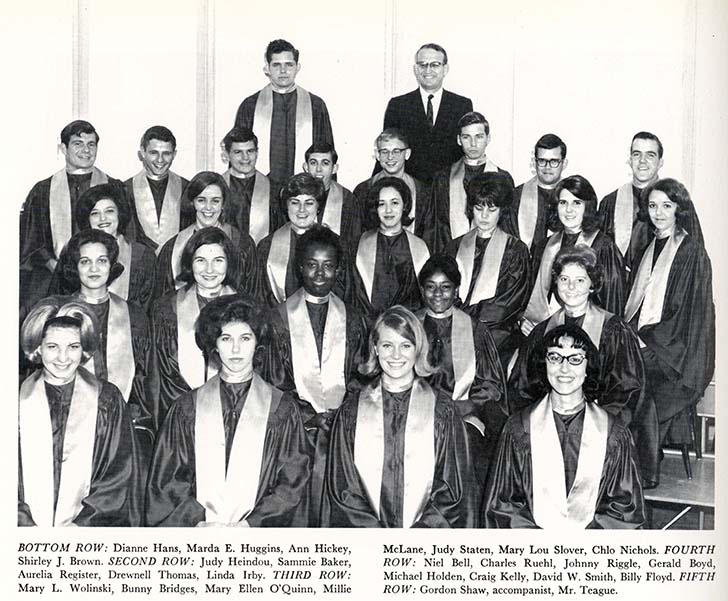

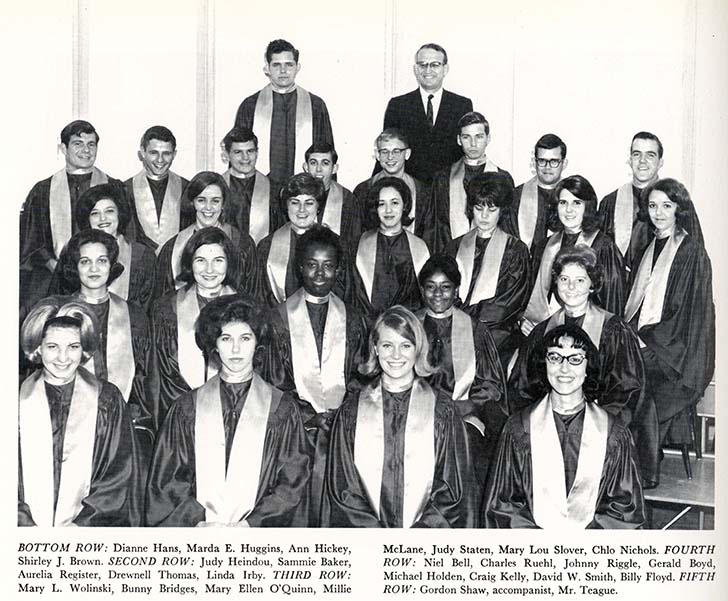

Integration, Year Three

Miss Thomas was most active in extracurricular activities. Here she is shown in the 1966 Glee club with Aurelia Register, the third African American student who entered the school in 1965-66. Perhaps because of her activities, Miss Thomas had encounters that Robert Pierce did not: "Unlike Pierce [she] had encountered open animosity in students, referring to ugly incidences of name calling from other students." (Campus Canopy, 5/4/67, p.4).

Glee Club, 1967

Integration, Year Four

At the end of their four-year journey, Robert Pierce, “who had turned down a scholarship to Morehouse College . . . to enter VSC because he felt it was something he had to do,” summed up his experience: “The atmosphere at VSC was quite different from what I had known in high school . . .I was used to having a lot of friends and participating widely in student affairs. However. . .I had anticipated this change and felt that at least I would have more time to concentrate on my academic studies, which would make up for the lack of activities” (Campus Canopy, 5/5/67). Both saw some change in student attitudes over four years, and both commended their professors for the extra help they had given.Thomas and Pierce went on to success with graduate degrees and careers in social work and health.

Integration during the 1960's

Drewnell Thomas and Robert Pierce, Senior Year, 1967

Joyce Joyce

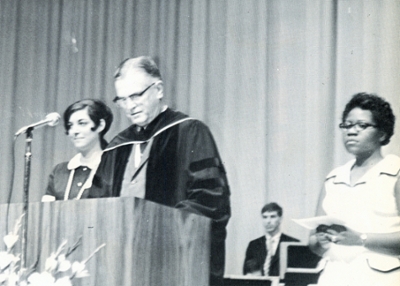

Desegregation at VSC in the sixties proceeded in a trickle. Entering as a freshman in 1968, Joyce Ann Joyce of Valdosta went on to graduate from VSC as the first African American Annie Powe Hopper Award winner. She returned in 1973 as the first African American English instructor, as shown here. Joyce went on to complete her Ph.D. at the University of Georgia in 1979 and has earned an international reputation as a scholar in African American Studies and Women's Studies.

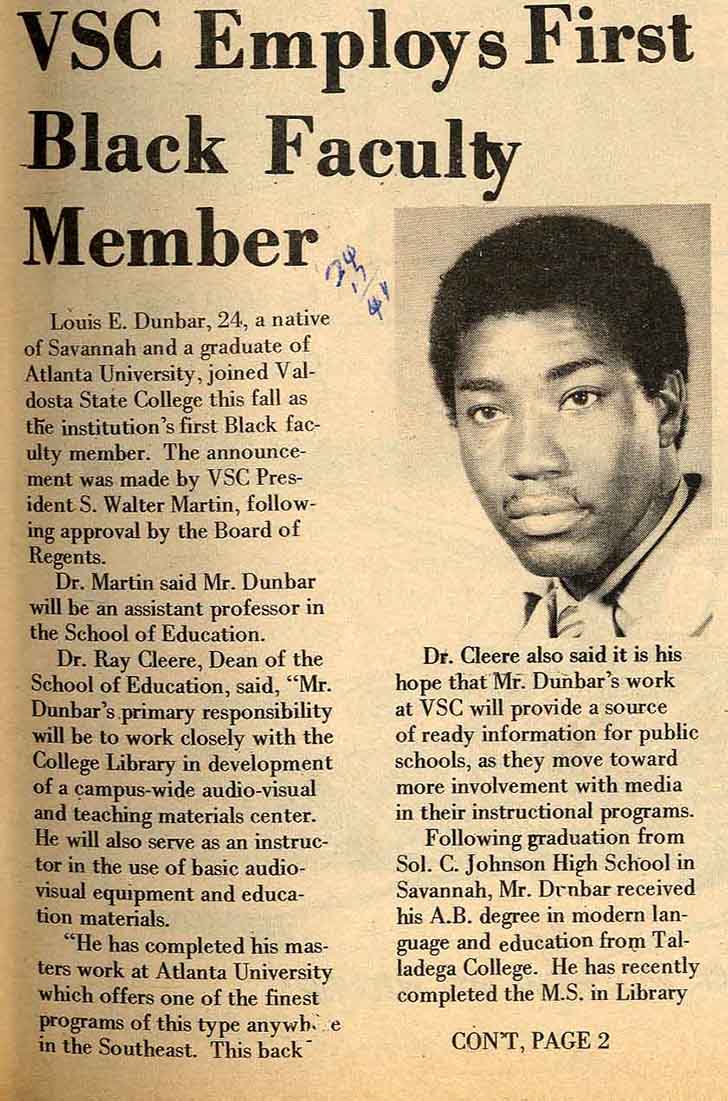

African American Faculty

As Desegregation spread throughout Georgia high schools by 1970, the numbers of African American students increased at Valdosta State, and African American faculty appeared on campus. In 1970, VSC employed its first black faculty member, 24-year old Louis Dunbar. The black administrator, Arthur L. Hart, followed in 1974.

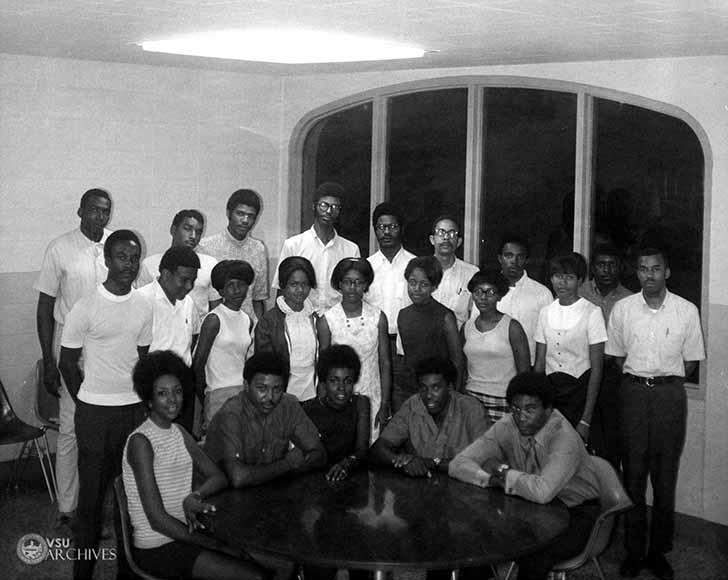

Black Student League

By 1970, a Black Student League formed on campus "to promote the ideals of human dignity, respect, and pride, to encourage cultural and historical awareness, to aid and encourage the underprivileged and the oppressed, to attack shame and hypocrisy wherever and whenever it appears."(Pine Cone, 1970).

Valdosta State College Black Student League, Founding Generation, 1971

Cultural Milestone

Just a little more than ten years after its initial desegregation, VSC crossed another cultural milestone of social desegregation when Skip McDonald of Adel became homecoming queen in February of 1974. Here is Skip McDonald, 1974 Homecoming Queen.

Skip McDonald, Homecoming Queen, 1974

- South Georgia Folklife

- African American Studies

- Mark Martin Collection

- Joyce Ann Joyce Collection | Joyce Ann Joyce Web Exhibit

- Amalia Amaki

- Songye African Art

- Eichberger East African Art Collection

- VSU Black Student League

- Leonard Long Civil Rights Collection

- Southern Patriot: Civil Rights Newspaper Index

- Valdosta State University African American Studies Integration Page

- "Negro Boy, Girl Here Quietly Attend VSC: Fist of Race Enter School Without Any Disturbances," Griffin, Tenney, Valdosta Daily Times, September 18, 1963.

- "VSC Employs First Black Faculty Member," The VSC Spectator, October 6, 1970.

- "Black Gets VSC Post," The Atlanta Journal and Constitution, June 23, 1974, 12-C.

- "Vote for Queen Friday," The VSC Spectator, 1974.

- "First Black VSU Grad Made Local History," Dean Polling, Valdosta Daily Times, April 21, 1994

- Valdosta State College: President's Annual Reports 1963-1975

- Southern Patriot - Civil Rights Newspaper

- David Williams Oral Histories | Women's Studies Oral Histories

- Slavery Papers and Speeches

- The Mary Turner Lynching

- Finding Aid for University of Georgia Integration Materials 1938-1965

Secondary Sources

Shelton, Melvin Anthony. The Politics of Race and Class and the Development of Public Education in Georgia: A Qualitative Study of Retired African American Teachers' Perspectives on Schooling From 1930 to 1970. PhD diss., Valdosta State University, 2004. Vtext (10428/463)https://hdl.handle.net/10428/463.

Archives & Special Collections

-

William H. Mobley IV Reading Room

Odum Library

1500 N. Patterson St.

Valdosta, Ga. 31698

archives@valdosta.edu -

Mailing Address

1500 N. Patterson St.

Valdosta, GA 31698 - Phone

- Phone: 229.333.7150

- Archivist

- Phone: 229.259.7756

Monday - Friday

8:00 am - 5:00 pm